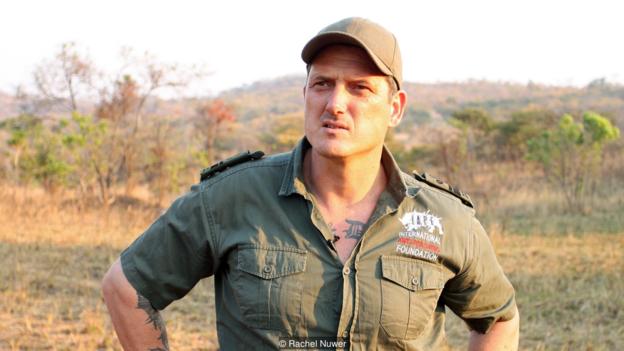

Imagine building your own army to tackle head on the injustice you see in the world. That’s exactly what former Special Ops Sniper in the Iraqi War, Damien Mander, decided to do.

While visiting Africa, Damien Mander saw the damage and destruction being done to our planet’s most endangered species. He decided he would do something about it. He sold his Australian investment portfolio and founded the International Anti-Poaching Foundation.

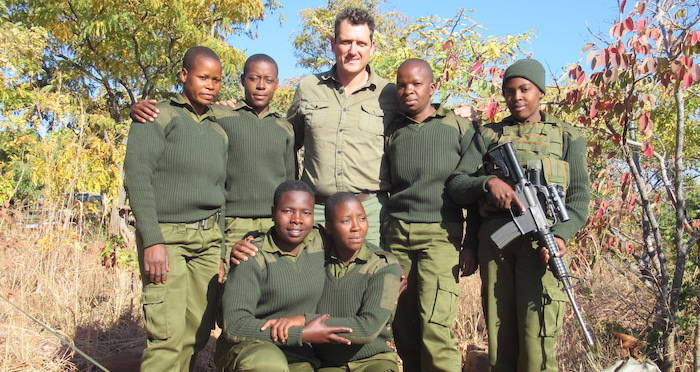

His army of 37 women in Zimbabwe protects elephants, rhino and other endangered species from poachers. He is expanding to Kenya, Mozambique and South Africa. Damien explains how he empowers women to protect animals and claims it has been one of the most important things he has ever done.

Accompanied by lead ranger Vimbai Kumire, Damien and Vimbai discuss the pride and challenges of defending animals on the African frontlines.

PHUNDUNDU WILDLIFE AREA, ZIMBABWE, JUNE 2018: Members of the all female conservation ranger force known as Akashinga undergo tough training in the bush near their base. Akashinga (meaning the ‘Brave Ones’ in local dialect) is a community-driven conservation model, empowering disadvantaged women to restore and manage a network of wilderness areas as an alternative to trophy hunting.

Many current western-conceived solutions to conserve wilderness areas struggle to gain traction across the African continent. Predominately male forces are hampered by ongoing corruption, nepotism, drunkenness, aggressiveness towards local communities and a sense of entitlement. The I.A.P.F, the International Anti-Poaching Foundation led by former Australian Special Forces soldier Damien Mander, was created as a direct action conservation organisation to be used as a surgical instrument in targeting wildlife crime.

Here is Damien on what it means to be a real man, a tough man, and strong man, a defender of the vulnerable and the innocent.

In 2017 they decided to innovate, using an all- female team to manage an entire nature reserve in Zimbabwe. The program builds an alternative approach to the militarized paradigm of ‘fortress conservation’ which defends colonial boundaries between nature and humans. While still trained to deal with any situation they may face, the team has a community-driven interpersonal focus, working with rather than against the local population for the long-term benefits of their own communities and nature.

Cut off from places of worship and burial, grazing areas, access to water, food, traditional medicine and given limited opportunity for employment or tourism benefits, it’s little wonder many of these communities struggle to see any value in conservation efforts.

Women have traditionally played major roles in battle and are now re-emerging as key solutions in law enforcement and conflict resolution. In the Middle-East, counterinsurgency operations that involve penetrating and working with the local population to try and win the hearts and minds have become fundamentally reliant on the nature, credibility and intuition of women to make critical inroads.

The front lines of conservation however have largely remained a man’s playground, culturally and ideologically isolated from the rest of the world. Despite the fact women do the majority of manual and household labor on the African continent, their inclusion in the field mostly seems like a token gesture. Sean Wilmore, President of the International Ranger Federation and Founder of The Thin Green Line Foundation estimates the ratio of men to women in frontline conservation roles in Africa is as distorted as 75-100:1.

“A growing body of evidence suggests that empowering women is the single biggest force for positive change in the world today.” Nature Conservancy. I.A.P.F integrated a full-time, entirely female staff from the local population to manage Phundundu Wildlife Area, a preserve owned by the community from where the women lived and previously set aside as a trophy hunting block.

In July 2017, 87 female candidates presented from the marginalised communal areas directly bordering one of Africa’s largest remaining elephant populations in Zimbabwe’s Lower Zambezi Valley. Selection was opened exclusively to unemployed single mothers, abandoned wives, victims of sexual and physical abuse, wives of poachers in prison, widows and AID’s orphans. By doing so, opportunity was created for the most vulnerable women in rural society. These are women who had never received a secure form of income; women who in some cases had their children taken because they could no longer afford to keep them. Some of those children taken were the offspring of serious sexual assault.

Upon opening a bank account and receiving their first paychecks, the women danced in the streets with their bank cards in the air. The UN, a driving force in closing the gender gap, highlights that around the world, “When women work, they invest 90 per cent of their income back into their families, compared with 35 per cent for men.” Melinda Gates, Co-Chair of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation recently wrote, “Research shows, however, that women are much more likely than men to buy things that set their families on a pathway out of poverty, like nutritious food, health care, and education… when a mother has control over her family’s money, her children are 20% more likely to survive… simply put, when money flows into the hands of women who have the authority to use it, everything changes.”

For a woman, family is almost everything. The opportunity to simply support their family brings a loyalty and passion in the work they do not seen in any other incentive. It surpasses fame, fortune, status and ego, placing the fate of conserving nature directly into the hands of women as ultimate protectors. With the positions they currently hold, the women don’t seem willing to jeopardise the opportunity they have made the most of by turning to corruption. Through choice, none of the team drinks alcohol, there is no sense of entitlement and remarkably, little to no ego. They don’t compete with each other, they work together and when one has a problem, they all have a problem. Problems jeopardise everything they have worked for and the future of their families and they will not tolerate this.

Following their deployment, I.A.P.F noticed that the women are proving extremely productive at de-escalating situations as opposed to antagonising them. The women seem more concerned with building and maintaining harmonious relationships with their local community. Subsequently, this is not just a unit of female rangers trying to protect an area, but rather a community of people who are motivated to support the protection of the preserve. The three interlocking streams of Akashinga focus on personal development, community development and conservation.

Respected, empowered and developing women are the fastest way to build more collaborative communities. Collaborative and motivated communities lead towards conservation becoming a byproduct of the first two functions. The women provide an efficient, effective and scalable model, which inspires and empowers other women in their communities, giving them opportunity to secure their own destiny, whilst safeguarding biodiversity. Despite being naturally fierce protectors, the woman ranger seem to be far less antagonizing and there is less need for a militant response meaning greater efficiency and smaller budgets. The model is currently spending around $1.47 per acre per annum on protection. A 2014 research paper on ‘Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems as a Rhinoceros Anti-Poaching Tool in Africa’ studied 13 different preserves and outlined an average cost of $8.06 per acre per annum in South Africa’s KwaZulu Natal, a 548% difference.

The all-female model continues to shift the paradigm of how business is done in anti-poaching and conservation. With the historical recruitment process of rangers being drawn from distances far away in order to reduce corruption, getting home has been a long journey often taken as little as once per year. When we send our soldiers into conflict we don’t expect them to be deployed for years at a time, yet rangers maintain such rotations away from their families for decades. By being able to recruit directly from the local community, these female rangers can spend far more time at home.

Dangerous wildlife such as elephant and buffalo seem far less aggressive towards all female patrols as opposed to mixed or all male patrols. Reports from the male unit that patrolled the area prior to the local demise of the hunting operation reported that antagonized elephants harassed them at least once a month. The women are yet to experience this phenomenon. Professor Victor Muposhi, head of the School of Wildlife, Ecology and Conservation from the Chinhoyi University of Technology (CUT) in Zimbabwe believes this behavior is most likely ingrained instinct after millennia of being hunted and killed by men, not women. As for the effectivenss of their policing, the women have arrested over 50 poachers so far, with an average of 9years sentencing for most of these poachers.

Across Africa, hunting areas make up a staggering one-sixth of all landmass across participating countries and these areas are often the most strategic, bordering communities and buffering National Parks. Reduced wildlife populations, tougher restrictions around the import and export of trophy’s such as Ivory, and increased activism are driving hunting into the ground. As funding from hunting into the conservation of areas decreases, many of these preserves and their neighbouring communities no longer receive sufficient benefits to motivate conservation. The areas being abandoned by hunters become susceptible to illegal mining, timber harvesting, poaching and human settlement. To continue preserving these areas and their significant biodiversity, communities need to be included in future models while gaining similar or greater benefits than what trophy hunting provided.

The Akashinga model being implemented does not intend to take on or take over trophy hunting, rather provide an economic alternative to areas where it is dying a natural death anyway by partnering with long-standing local stakeholders and traditional leaders. Through activism, the West has largely been responsible for helping to drive a downturn in trophy hunting. With that movement having an increasing impact on the industry, we need to turn to the West again for support of alternative models to protect the areas subsequently being left vacant. “

The women rangers on project have also converted to veganism, further acknowledging their responsibility as conservationists to animals and the environment. Looking back on their individual harsh backgrounds they were vulnerable and victimised. They are now in a position of authority and have chosen not to unnecessarily project power or force over anything else, animals included. Taking the long view on this, the more people replacing meat with healthy plant-based options in rural Africa will mean less bush meat poaching and the less grazing of cattle in and around wilderness areas – two key issues conservationists face and a frequent flashpoint in local communities who often struggle for sufficient water and food to sustain their cattle. It’s ironic that a small town called Nyamakate (meaning the ‘meat pot’ in local Shona dialect) would become the home of a grass roots vegan movement in rural Africa. The vegan movement is surprisingly un-represented in conservation circles.

With an estimated 56-150 billion animals killed annually, our desire to eat meat is the single greatest global cause of suffering. According to The Union of Concerned Scientists, a renowned US non-profit science advocacy organization, Beef production uses more agricultural land than all other food sources combined and regards the overall meat industry as the second-greatest environmental hazard facing our planet behind fossil fuelled vehicles.

An independent report from research firm GlobalData indicated a 600% increase in USA consumers claiming to be vegan from 2014-2017. Whilst the United States may be quite a distance from the plains of Africa, her purse strings are not. The majority of IAPF’s and many other conservation organisations funding comes from the USA. With philanthropists such as Sir Richard Branson investing in alternatives and predicting that meat will largely be a thing of the past within three decades, the plant-based movement is going to continue as one of the fasted growing food sectors and wield increasing financial influence – particularly where the protection of animals and environment is concerned. It’s worth noting that in 2017 I.A.P.F attempted to negotiate with an all-male anti-poaching unit they had run for 7 years to trial a vegan diet. We offered them any food substitute that was available, a chef rather than preparing their own meals and eventually, a financial incentive. The sentiment bordered on mutiny and a resounding “no” to any vegan trials. The women simply agreed to what was initially a trial and went about their jobs.

SUBSCRIBE to Awesome Vegans with Elysabeth Alfano on iTunes. My Youtube Channel, Elysabeth Alfano. And be sure to subscribe to my monthly newsletter. Never miss a Facebook Live interview session or live cooking demos. Plus, Instagram and

Twitter .

Thank you to WGN Radio which airs all of the Awesome Vegans Podcasts! In addition, Elysabeth can be heard live on WGN Radio hosting, Nightside, from 11p-1a, periodically every month.

Thank you to VegFund for supporting this podcast.